Good Morning,

This is the second part of my summary of Range. Read Part 1 here.

The Trouble with Too Much Grit

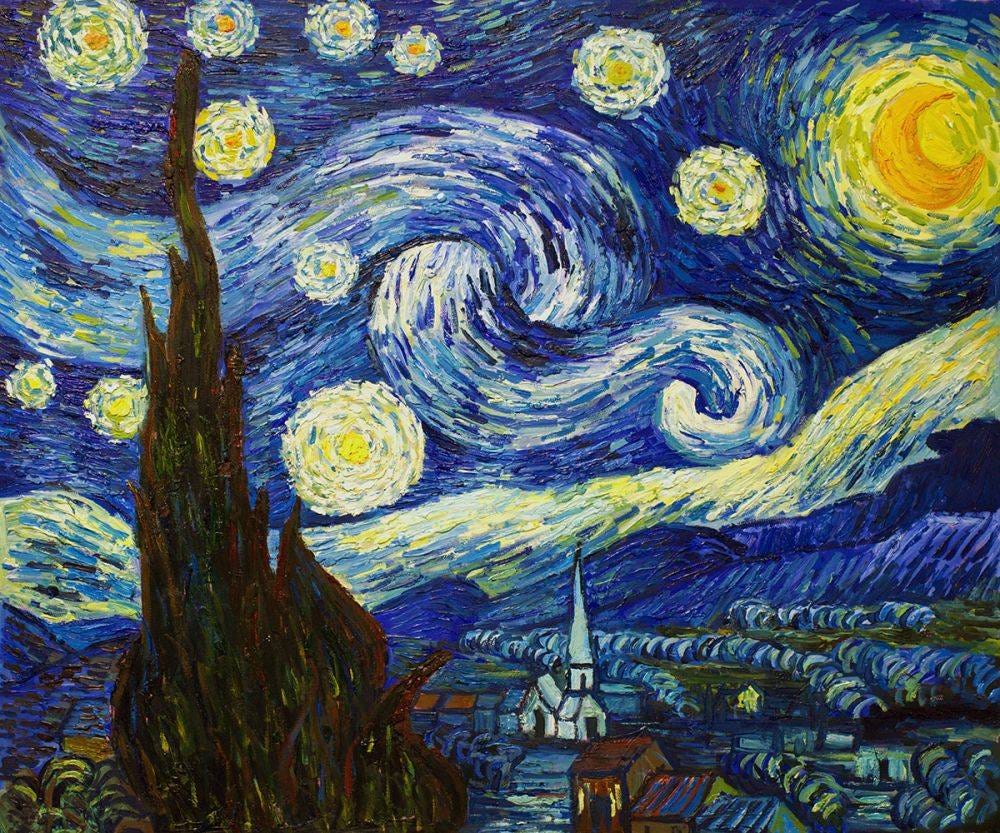

One of the greatest artists in history had an exceptionally late start. As a boy he was terrible at drawing and didn’t enjoy lessons. Later he would go through various professions: art dealer, teacher, a prospective pastor etc. Trying and seemingly failing at all. At 27 he lost hope in his passion of becoming a pastor. After his failed efforts he began to develop an interest in drawing again. At 33 the man enrolled in an art school, but again did not last more than a few weeks. He entered a drawing competition where the judges told him he belongs in a beginner’s class with 10 year old kids. But he continued with art. As with his various career attempts, he swung between wildly different forms of art, feeling passionate about one, then dropping it for another style the next week. One day he pulled out an easel and oil paint – which he had no experience with – and discovered he was great at it.

When he was younger, the boy’s mother worried for him as he would spend hours outside, observing the skies and the landscapes, sometimes spending hours in a storm. Now with his paintbrush in hand, he gazed out his window again, and painted the sky on that starry night. The paintings of Vincent van Gogh – who was once relegated to children’s classes – have sold for hundreds of millions of dollars today.

Many great artists and authors of history have similar stories of late starts.

In many fields where high quality individuals – such as the US military – are sought out, candidates are judged based on a grit test. Measuring people based on their grit and ability to stick it out, discourages sampling. Perhaps if Van Gogh had more grit, he’d have stuck to his original career choices, and we’d never know his name.

Strategically quitting things to explore other options seems like a bad move the further we are in our careers and lives. This is the sunk cost fallacy. It can sometimes be more valuable to be behind the curve but discover something you’re truly passionate about.

Flirting with Your Possible Selves

As a teenager, Francis Hesselbein dreamed of becoming a playwright. However, due to her father’s untimely death she had to drop out of college and support her family at 17. At 35, she was asked to take a volunteer role leading a troop of Girl Scouts. She was hesitant at first, but she accepted and spent her time learning about the organization. She spent the following years of her life going between volunteer roles with Girl Scouts. One day she was asked to become the Executive Director of the local Girl Scouts council. Francis was again hesitant; she had no college degree and no work experience. She finally agreed to fill in for 6 months, beginning her first professional job at age 54. As society changed in the 60s and 70s, the Girl Scouts organization in America began to see fewer girls becoming members. After some leadership turnover, the CEO position for the organization was empty for almost a year. The search committee eventually gave Francis a call, asking to interview her for the role. The previous CEOs had been very accomplished women with PhDs and various professional experiences. Once again, she relented and accepted the position. Francis Hesselbein had no college degree nor any professional job until age 54. Today – at 104 years old – she holds a Presidential Medal of Freedom and 22 honorary PhDs, and multiple experiences running organizations. Renowned management consultant Peter Drucker called Francis the greatest leader in the country, saying “She could run any company in America”.

Many of us make big decisions about what we’d like to do at an early age. Even while knowing that our desires and beliefs changed so much in the past, we believe they won’t change in the future. This is the “end of history” illusion.

Neuroscientist Ogi Ogas describes the standardization covenant as the cultural idea that it’s better to specialize early than to sample various options as a path to success. However, he found that the most successful people took winding paths to success. They don’t worry about falling behind, and simply look for where they fit best.

Francis’ case is a testimony to the idea: who we are today does not have to define who we will be tomorrow.

The Outsider Advantage

Alph Bingham, an organic chemist, recalled his graduate school experience working with other students. They were tasked with finding ways to create particular molecules. He noted that the cleverest solutions would always come from ideas outside the curriculum. One day Alph’s solution was the cleverest. He came upon an elegant solution by comparing compounds to cream of tartar, an ingredient he remembered from his childhood.

Years later when Alph was the VP of research at Eli Lilly, he employed a new method to solve difficult problems. He decided to take the challenges which stumped scientists at the company and post them online, letting anyone solve them for a reward. When the other scientists saw their problems posted online, they doubted outsiders could solve the problems which stumped qualified scientists. Alph’s wager was correct, many people with various backgrounds sent in solutions.

Based on this idea, Alph later created the company InnoCentive, which facilitates the same outsider solution platform for other companies. NASA spent 3 decades trying to predict solar particle storms. When they posted the problem publicly through InnoCentive, it was solved in 6 months by a retired engineer.

InnoCentive works because specialists become so narrowly focused, it becomes difficult to think outside of the box. The outsiders have the advantage of not being inhibited by the method of thinking which keeps professionals stumped.

Lateral Thinking with Withered Technology

In the middle of the 20th century, a Japanese company that sold playing cards was struggling. As Japanese society gravitated to other forms of entertainment, Nintendo Co. became less able to make money off of their cards. In 1965, the company’s president hired a young electronics graduate, Gunpei Yokoi, for maintenance on card printing machines. Yokoi struggled during his degree, graduates who did better had their eyes on bigger companies and didn’t apply to Nintendo.

Yokoi was a tinkerer; he spent a lot of time building different contraptions. At work he built an extendable arm to grab things lazily. When the company’s president saw this, he was struck with an idea: what if this arm could be used in a game? This was the birth of Nintendo’s first toy, “Ultra Arm”. From then on, Yokoi was no longer working in maintenance, he was in charge of the company’s research and development.

Yokoi employed what he called “Lateral Thinking with Withered Technology”. Lateral Thinking is the application of existing concepts in new ways. Yokoi graduated at a time where electronics were developing at exponentially faster rates. His approach to innovation was to reimagine new uses for old technologies. This thinking is what led to the creation of the Game Boy. From a technology standpoint the Game Boy was not even close to the competing consoles from larger competitors Sega and Atari. Yet it was wildly more popular. The older technology allowed for a smaller, cheaper, and reliable product.

While others focus on the newer and more narrow views, rethinking old ideas can make you the most innovative in the room.

Fooled by Expertise

Penn State University professor Phillip Tetlock studies experts. He examined almost 300 forecasts made by experts, predicting political and economic trends. He found that despite their years of experience and doctorate degrees, the average result of these forecasts was horrible. Most experts were terrible at forecasting.

In 2011, the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) held a 4 year prediction tournament. Teams could be formed however they wanted. Every morning for 4 years, new predictions could be submitted. Questions included stock price estimation, predicting whether a country would leave the EU.

Most teams consisted of experts just like those that Tetlock studied. However, he and his wife Barbara Mellers – also a psychologist and scholar – created their team purely by recruiting volunteers. Anyone was allowed to apply and after screening 3200 people, they selected those who did best at forecasting. This group was not full of PhDs, just people with diverse knowledge and experiential backgrounds. They destroyed the competition.

It can be incredibly valuable to foresee trends in the economy, politics, technology, and science. Those with the foresight on these ideas can innovate and solve problems more effectively. However, when we seek these predictions, we turn to narrowly specialized experts, when it may be better to have a diverse group of non-experts.

Learning to Drop Your Familiar Tools

In the 1990s, there were 4 separate wildfires in which 23 firefighters tragically lost their lives. Organizational behavior expert Karl Weick noticed something unusual about these deaths. Firefighters who did not manage to safely outrun a fire were found with their tools still on their person. Even when running from a blazing wildfire, they were so overtrained to keep their tools, they held on to them, which slowed them down. Two separate analyses conducted on the fires concluded that if they had dropped their tools, many of them would have survived. A survivor later said “[I] realized I still had my saw over my shoulder! I irrationally started looking for a place to put it down where it wouldn’t get burned. . . . I remember thinking I can’t believe I’m putting down my saw”.

Interventional Cardiologists specialize in a particular surgery which uses stents to keep blood vessels open. However, recent research has shown that the use of stents isn’t more effective than medication and lifestyle changes (https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2019/11/invasive-heart-treatments-not-always-needed.html). Yet because these cardiologists have specifically learned to use this tool, they might still opt for an invasive surgery, even when it’s ineffective.

“Dropping one’s tools is a proxy for unlearning, for adaptation, for flexibility,” Weick wrote.

In order to solve problems and think outside the box, one needs to learn to drop their familiar tools. It’s hard to accept that the things we’ve specialized in might not be the solution to the problems we face. But adapting and accepting new ideas is crucial in an ever changing world.

Deliberate Amateurs

Oliver Smithies worked in a lab in Toronto, looking for a precursor to insulin. On weekdays he worked in the lab as usual. However, “on Saturday,” he said, “you don’t have to be completely rational”. Smithies set aside Saturdays for experimenting in unorthodox ways.

One week the lab was stuck on a problem with molecule separation. They initially used an electric current through a special type of paper, but insulin stuck to this paper and did not separate. During Saturday experimentation with paper alternatives, Smithies remembered something from his childhood. He remembered his mother using starch to stiffen shirt collars when she ironed, and later asked him to dispose of the starch. When it cooled, the starch would make a jelly like substance. He made a starch gel and tried it in place of the paper. When he applied a current, the insulin molecules separated. His idea of using starch for gel electrophoresis revolutionized biology and chemistry research.

University of Manchester physicist Andre Geim (with no relation to Smithies) also set aside “Friday Night Experiments” for testing out interesting ideas. One of these Friday experiments earned him the Ig Nobel (not associated with the Nobel Prize), a satirical award for comical and trivial scientific achievements. He won it for making a frog levitate using magnets (The water molecules inside frogs orient themselves to repel magnetic fields). In another Friday night experiment, Geim used scotch tape to pick up thin layers of graphite which is used in pencil leads. For this, Geim and his PhD student won the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery of graphene, a material 100,000 times thinner than hair and 200 times stronger than steel. Graphene was theorized for decades and previously only observed through electron microscopes, with no well known method to produce it. Geim produced it using a method you could replicate at home today with a pencil and tape.

Taking common ideas from one place and applying it to another can be revolutionary and innovative. Sociologist Brian Uzzi calls it an “import/export” of ideas. He found that “scientists who have worked abroad—whether or not they returned—are more likely to make a greater scientific impact than those who have not”.

Uzzi and his team examined 18 million research papers from different scientific fields to see whether uncommon knowledge combinations mattered. They found that most of the papers which went on to receive a large number of citations from other scientists, tended to draw some aspects of their work from unconventional sources.

Another team examined half a million papers and classified a paper as “novel” if it made a new combination (i.e. cited 2 other journals which had never been cited together before). Only 10% of papers made these novel combinations, and only 5% made multiple of them. They tracked these papers over time, and found that upon publication these novel papers were mostly ignored and published in less prestigious journals. Although within 3 years of publication they would gain more citations than the conventional paper. Within 15 years, studies which made multiple new combinations were significantly more likely to be in the top 1% of most cited papers.

Arturo Casadevall – Chair of Molecular Microbiology & Immunology at Johns Hopkins – believes that science research is in crisis. He believes young scientists are rushed to specialized “before they learn how to think”. Today’s research funding and journals don’t encourage true innovative behavior.

Japanese biologist Yoshinori Ohsumi closed his Nobel acceptance speech with:

“Truly original discoveries in science are often triggered by unpredictable and unforeseen small findings … Scientists are increasingly required to provide evidence of immediate and tangible applications of their work.”

Casadevall encourages people to regularly read and learn outside of their field. He tells them, “Your world becomes a bigger world, and maybe there’s a moment in which you make connections.”

Expanding your Range

When people hear that most great athletes, musicians, artists etc. are not early specializers, but late starters, they ask: What should be done instead then?

This book stems from an effort to try and answer that question, which is difficult to answer in one sentence. There is no formula or method to follow, but there are notable similarities in the examples of many great people with wide range.

Most renowned creators made a large amount of works, from which only a few ever became huge successes. Thomas Edison held over 1000 patents and was rejected for many more. Yet only a handful of those were revolutionary and innovative.

Innovative ideas tend to come from a path of disorderly experimentation. Perhaps have your own version of Friday/Saturday experiments.

If there is one sentence which should be followed, it’s: Don’t feel behind. Allow yourself to experiment and learn various things while others specialize.

“It is an experiment, all of life is an experiment”

- Oliver Wendell Holmes

Thank you for reading. I hope you enjoyed the summary. If you want to read some more anecdotes David Epstein provides, I recommend getting the book, it was an excellent read.

If you enjoyed this issue, please leave a like. If you liked it enough to share with others:

I would love to hear your thoughts on today’s post,

You can also hit me up on twitter @h__sid

Thanks for reading,

Sid